ICU Research and Consent: A Forum for the Future

In August 2023 we hosted a forum to discuss our findings from Critical Care Futures, and to open up discussion with a wider audience around the sensitive areas of the use of patient data for research, and consent for acute research in the case where an individual is unable to consent for themselves.

We invited ICU survivors and their relatives, clinicians, researchers, and ethics committee members, as well as our colleagues from the Emergency Department. We were also joined by a representative of the Scottish Government’s Working Party for Adults with Incapacity.

This was an interactive afternoon, where people drank from our Critical Care Futures mugs and used our pens to write post-it notes with their comments. We explored different types of research, with their different risks, and how processes differ in Scotland from England and Wales. We heard from Goutam Das who gave an account of his stay with us in ICU, and his thoughts on research for critically unwell patients. We finished with a facilitated discussion with Dr Charles Wallis, Professor Tim Walsh, Mr Goutam Das, Dr Corrienne McCulloch and Dr Catherine Montgomery around possible futures for research in ICU.

We were extremely fortunate to have Tess MacKenzie with us to tease out the afternoon’s discussions and themes (left) in real time.

Critical Care Futures is a public engagement project funded by ScotPEN Wellcome Engagement, that creatively involves a range of professional and public ICU stakeholders in dialogue about the boundaries between research and care. Its goal is to influence our approach to critical care research in the future, as well as to create evidence to support the use of creative methods of public engagement in health research.

Who was involved

The core team:

Annemarie Docherty – academic Critical Care Consultant, University of Edinburgh

Catherine Montgomery – Sociologist of Science and Medicine, University of Edinburgh

Corrienne McCulloch – Clinical Research Nurse Manager and NRS Clinician, NHS Lothian

Andthen – Santini Basra, Freyja Harris, Lizzie Abernethy – a team of design researchers who specialise in conducting research about people’s perspectives on the future

Stakeholder partners:

Goutam Das – recent experience of life as a patient in Critical Care

Joanne Mair – Clinical Project Manager with various roles as part of the NHS ethics committee service.

Monika Beatty – Consultant in Critical Care, NHS Lothian

Jean Antonelli – Trial Manager in the Edinburgh Clinical Trials Unit within The Usher Institute of Population Health Sciences and Informatics, The University of Edinburgh

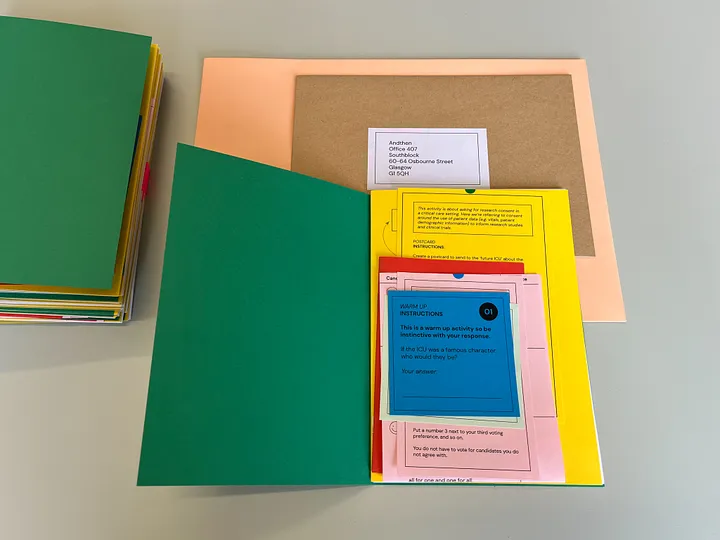

Cultural Probes — a creative approach to engagement

Our project seeks to challenge the traditional relationship between the researcher and the research subject. To do so, we are using a tool from the field of design research called ‘cultural probes’. These probes are kits containing

tasks such as photographing, mapping, creative writing and postcard-making that encouraged participants to observe, reflect on, and share their experiences, values, and beliefs. Patients, relatives, clinicians, researchers, and research

governance staff completed the probes individually and then discussed their results in a group setting. This has allowed us to explore new possibilities and catalyse conversations in a way that upended the existing dynamics between

these groups and created space for new thinking about how critical care research could be different.

What’s the output?

The project has generated a range of interesting perspectives, new ways of thinking, and generative exchanges between stakeholder groups. From this, we have generated a set of future principles for research in critical care, which summarises the perspectives of those we engaged in this project with a specific focus on their views on data, consent, and patient-centred approaches to research.

We have also produced a range of artefacts on which are included some of the more provocative questions or conversations that came out of this work, which have been installed in the space around you — you might find yourself signing a form with a pen which challenges you to think about what ‘informed’ consent really means, or you might find yourself sipping your tea out of a mug which suggests new forms of value exchange between patients and researchers.

Please read about our findings and thoughts for the future in full in the report below.

Below is a series of blog posts which chart our experiences to date in this project.

Blog 5: Designing public-facing outputs for Critical Care Futures

Introduction

From the outset of this project, our goal has been to communicate the key learnings, themes, and questions to the public in an ICU setting. Due to the unpredictable nature of cultural probes, we were unable to anticipate responses to the tasks, and therefore, we could not define the form of the output from the beginning. We instead began exploring options for how to present some of the emerging themes to a wider audience after receiving all the probes and hosting debriefs to generate insights and principles.

Designing the public-facing output

Initially, the team explored various output options. However, once an ICU waiting room was deemed the most appropriate environment, some key design considerations were raised that shaped our thinking, resulting in the following brief;

- A sensitivity to the emotional state of those interacting with it or in the space

- No rigorous maintenance

- Robust enough to endure multiple uses

- Easy to clean and appropriate for a sanitary environment

We explored various roles and forms for public-facing outputs, such as sharing participant voices, illustrative representations of a future ICU, artefacts that engage people with project themes and questions, and activities that encourage reflection on the principles.

We felt it was important that the content was centred on participants’ voices within the project and communicated some of the provocations that had arisen from the cultural probe engagement.

Ultimately, we chose intentionally mundane objects, pens and mugs, as the vehicle for this content. The idea was to choose objects that were not only synonymous with promotional material but also had utility within the environment and therefore would likely be spontaneously engaged with.

Producing and Installing the public-facing outputs

We chose the following designs for the mugs and pens, excited by their potential to be used in unexpected but relevant situations. For example, a pen questioning what “informed” consent really means might be used to collect consent, or a mug challenging the existing consent model might make its way into the hands of an ethics committee member. Our sincere hope is that these subtle yet provocative objects will inspire a new wave of discussion around data use and consent in the ICU.

We have produced these objects in large quantities with the goal of installing them in several ICUs, without framing them as final outputs. We will accompany them with posters that contextualise and explain the work. These posters are available for download now.

As this blog post is published, these artefacts are being installed in Critical Care in the Royal Infirmary Edinburgh with plans to install them in other Critical Care Units and academic settings.

Blog 4: Generating Insights

Introduction

After giving the participants a few weeks to complete the activities, we started to look forward to the envelopes of completed probes arriving back to us in the post. As we started opening and reviewing these responses, we were struck by the level of detail, and wide spectrum of meaning that was contained in each response. In some cases, responses were quite literal and easy for us to interpret, but others were metaphorical, or packed with personal meaning and challenging for us to unpack.

Debriefing Participants

In order to better understand the nuances of the probes, we arranged a debrief with participants to give them an opportunity to talk us through their responses and elaborate on any key themes. While cultural probes would typically be debriefed through one-on-one calls, we were keen to use this as an opportunity to bring together our participant groups (survivors, relatives, researchers, clinicians, and ethics committee members) who don’t typically meet outside of a clinical setting, and create space for unexpected interactions and conversations. In order to do this, we organised a debrief workshop, in which participants could compare responses and sensemake together. We also had an ambition to work with participants to collectively shape a set of principles for the future of research in critical care, and the workshop setting offered a good opportunity to produce a draft version of these which could be synthesised later.

The workshop was attended by 15 people, including patients, family members, ethics committee members, clinicians and researchers, who were divided into four groups. Each group was facilitated by a member of the project team, and those who co-designed the probes also attended to support discussions. We also ensured there was a mix of survivors, relatives, researchers, clinicians, and ethics committee members at each table to encourage healthy debate.

During the two-hour workshop, the groups covered discussions on topics such as what values should underpin the approach to research in critical care, how research can support a caring environment in critical care, how patients’ data should be accessed and protected, and how consent should be obtained for research in critical care. Each discussion concluded with a quick exercise to propose principles summarising the group’s discussion for the future of research in critical care.

At the end of the workshop, we arranged the suggested principles into groups and themes. We all — project team members, co-designers and probe participants — reflected on them and voted on the groups we felt most strongly about.

For those who were unable to attend the workshop, a debrief call was arranged that mirrored the questions asked to the group as a whole.

Synthesis

After digitising the workshop post-it notes and clusters of draft principles, the project team met to synthesise the principles further. We further discussed and refined these to ensure they each made a distinct point and reflected on the breadth of discussions covered in the debrief and across probe responses. This involved reviewing probe responses and affinity mapping specific responses using the draft principles as a guide. The final principles are as follows:

Blog 3: Cultural Probes in the Wild

This blog goes into detail about what the recruitment process looked like, how we managed the cultural probes whilst they were with participants and what we learned from the process. You can also find a link to download a blank version of the cultural probes we designed.

Recruiting Participants

At the beginning of any recruitment process, we create a recruitment framework to identify the groups of people we would ideally have involved in the research to ensure that the different perspectives we’re trying to reach are balanced. For this project, our recruitment framework was relatively simple — we wanted to recruit 20 participants equally across 4 groups:

- former patients or family members

- research ethics committee (REC) members

- clinicians

- researchers

It takes a lot of energy to recruit participants and it is important to establish clear communication and build a trustworthy relationship from the start. Annemarie Docherty and Corrienne McCulloch were responsible for identifying and approaching potential participants. Fortunately, they had well-established professional links with the clinical and research communities in critical care, making it easy to identify and approach potential participants from these groups. Consideration was given to recruiting a wide range of participants to bring different perspectives, for example, different professional roles in critical care and research.

Corrienne had previously spent a number of years coordinating and working with a critical care Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) group as well as involvement in the ICUSteps Edinburgh support group to connect us to past patients and family members. In the early stages of the project design and pre-grant award, a call went out to the PPI group to help review the project. Those who were interested in the project at that time were invited to participate as well as extending the invite to the wider PPI group.

The project was also advertised via the Chair of ICUSteps Edinburgh to enhance recruitment further in this group. This was successful and resulted in 2 participants with a recent stay in critical care volunteering their involvement. However, another participant who volunteered via this route withdrew during the cultural probe study due to the challenging nature of going back over their experience in critical care.

The most challenging group to engage were members of ethics committees, as, other than one of the co-design collaborators being a member of a research ethics committee (REC) there were no direct contacts or previous experience in the team to support recruitment here.

The opportunity was shared with a REC which reviews critical care research involving adults with incapacity and found one participant, and another was found through word of mouth. However, whilst recruiting for the other groups in the project, it became apparent that participants came with multiple identities. For example, research-active clinicians with personal experience of having a family member in critical care. Others had recent and current experiences of being a REC member alongside their other perspective(s) and this helped us to meet our target recruitment numbers. On reflection, if there had been an opportunity to attend and present the project at a REC this might have been more successful and personal than a forwarded email. In the other groups, established relationships and conversations about the project made recruitment much easier.

Corrienne followed up with all those approached to send through information on the research project and to share a sign-up link. There is always further follow-up with people to encourage participation despite an interest to take part having been informally expressed. The baton was then passed to Andthen for one member of the team to follow up with everyone. This worked well and ensured that all participants were receiving the same information and there was a standardised process for onboarding people into the research.

Managing the Cultural Probes

The onboarding process involved; collecting the postal addresses of participants, sharing further details about what the probes would contain in order to make sure the participants felt comfortable with the ask, making sure everyone understood the instructions and confirming whether there were any specific accessibility barriers involved in taking part.

Accessibility was a consideration from the beginning of the design process for the cultural probes. This involved anticipating the barriers that people might face — such as technical ability — as well as testing the tasks with the co-design group to gauge how easy the tasks were to understand and complete, or if any other unanticipated challenges came up. This highlighted things that needed to be changed such as making the tasks accessible to people with English as a second language and the varied preferences of a group that ranged from those who enjoyed completing the open-ended tasks and those who found them challenging to respond to.

Once the design process is complete, it is also important to be aware of any specific accommodations that can be made for individuals as well. Working with participants who have experience of being in ICU may have cognitive, physical or mental health impairments occurring as a result of their critical illness (known as Post Intensive Care Syndrome). This means that a flexible approach needs to be taken to how people respond to the research activities.

Once the probes were posted out we maintained contact with all participants to track the progress of each cultural probe. This included; ensuring packages had been received, being available to answer clarifying questions about the activities, helping people build confidence in their ability to complete creative tasks and confirming the receipt of the packages once they had been returned.

Some of the difficulties we came across when the cultural probes were out in the wild included; materials being triggering for participants, post getting lost in both directions, navigating delays with ongoing postal strikes and accessibility barriers around using pen and paper as the medium to complete the tasks.

Learnings from the process

- Having good relationships with potential participant groups is really useful when trying to bring people into a research project, particularly when it is a new process that is being tested.

- It takes much more energy and the success rate is much lower when recruiting a new or unfamiliar group of people. It is important to try to create personal connections here when possible.

- People are generally familiar with receiving things in the post and therefore there is a lower barrier to entry than with digital alternatives, particularly when trying to gain creative responses from people.

- The process of posting cultural probes is less direct and much slower than online correspondence. There are risks of the post getting lost which can be very demoralising for participants, particularly if they have put a lot of effort into their responses. It is also important to ensure there are time contingencies for when things go awry.

- Putting energy into designing and making the cultural probes visually interesting makes it more like receiving a gift than a burden to complete. Therefore, participants are more likely to put more energy and consideration into their responses.

- There are always accessibility challenges with cultural probes, no matter what medium they are offered in, due to the need for them to be standardised for a group but also individually accessible. In this case, completing activities on pen and paper became a barrier for some participants and in these cases the debrief discussions became really important to ensure that their opinion was equally heard.

- The cultural probes by nature will be completed by participants without researchers or facilitators present and therefore you’re likely to receive different responses to what you’d receive if they were being steered through activities.

- The ask and set-up of the tasks need to be really clear as nobody will be there to facilitate the activities. Particularly, when asking adults to complete creative tasks there needs to be an assurance that there is no pressure when it comes to artistic ability.

- Exploring research within critical care touches on highly sensitive experiences, especially for those with experience being a patient in critical care or being close to someone in critical care. We had to reflect this in the design of the probes. Because we would not physically be there in the room to facilitate their completion, we needed to ensure the probes weren’t so open-ended that participants would start exploring unsafe or triggering topics. While in another project, the cultural probes produced may have been more open-ended, here we went for quite contained probes with quite well-defined boundaries for exploration.

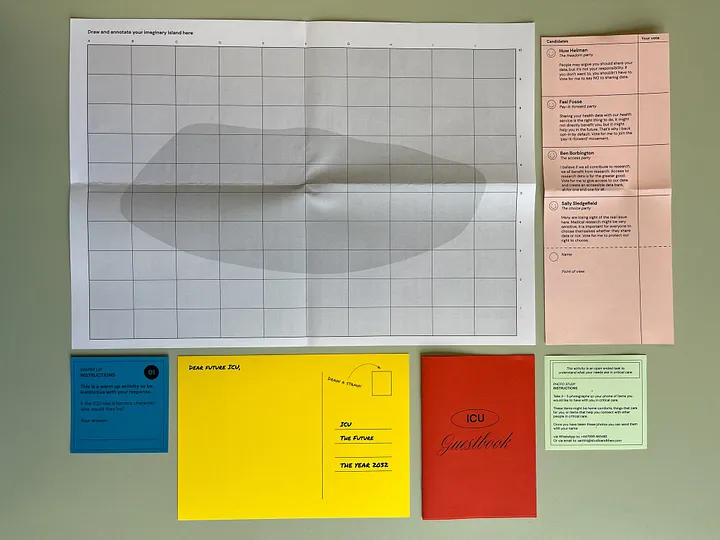

Sharing tools from our process

Some of the tools we developed to support this co-design process are available here to download for free, under a creative commons licence.

These include:

- Instructions

- A Warm-Up Activity

- The ICU Guestbook: Understanding what care feels like in the ICU to understand where research can add to the care people receive

- A Ballot Paper: Exploring different points of view on research in critical care

- Photo Study Instructions: Identifying items that you would like to have with you whilst in Critical Care

- Data Island: Exploring how patient data should be kept

- A Postcard: Understanding points of view on consent in research

Blog 2: Co-designing Cultural Probes

In this post we reflect on the process of designing cultural probes for this project. Cultural probes are complex research tools — there is a huge spectrum of possibility regarding the shape that they can take, and several factors need to be balanced in order to produce one which is appropriate and effective.

In our process, we brought together a diverse, interdisciplinary group to co-design the probes — the group was made up of four ‘co-designers’ who worked alongside the core project team. These co-designers represented the four intended audiences of the engagement activity:

- ICU Survivors and/or Relatives

- ICU Clinicians

- ICU Researchers

- Ethics Committee Members

Together we collaborated on the generation and then refinement of concepts for the probes, and then subsequently the four co-designers helped us test and iterate the first versions of these.

This post brings together three individuals who were involved in the co-production of the probes to reflect on the challenges and process from their own perspectives:

Catherine Montgomery is a Sociologist of Science and Medicine at the University of Edinburgh.

Santini Basra is the director of Andthen, a team of design researchers who specialise in conducting research about people’s perspectives on the future.

Joanne Mair is a Clinical Project Manager who focuses on the translation of novel diagnostics from bench to bedside. Joanne has also undertaken various roles as part of the NHS ethics committee service.

Santini: It’s been lovely collaborating with you both over the last couple of months to design these probes. I’m interested in learning about whether this has been a familiar experience for the two of you — both in terms of working collaboratively in this way, and contributing to the development such an open-ended exploratory research tool?

Catherine: For me, this has felt close to the ways in which I’ve done research in the past — engaging with key stakeholders, working in a multidisciplinary way, being led by what comes up (open-ended research is a mainstay of the sociological work I usually do). What has been less familiar, and really enjoyable, is the flipped power dynamic at work — rather than ‘steering’ this, being a participant in the process myself. Jo, I wonder how this has felt for you?

Jo: This is quite different to how I have carried out or been involved in research in the past. Although I engage with stakeholders and the end-users of the “product” they come from quite defined walks of life and set out with a specific aim which is normally to fulfil milestones in a grant. Within my ethics role, we work within a provided set of information over which we also have a very defined role. I really enjoyed the way everyone involved in this project was asked to look at it from their own perspective and expertise but also from other peoples’ and how they would engage, use and reflect on the outputs.

I feel that the openness of the collaboration allowed the team to explore the probes from all angles without feeling they had to be an expert in what they were saying, was that similar for yourself Catherine?

Catherine: Yes, it was. What worked really well was getting everyone around the table together — former patients, ethics committee members, researchers, clinicians and designers. This doesn’t often happen and I think the very act of getting people in the room together unlocked an energy and a mutual curiosity that helped shape the development of the probes in a very positive way. The kinds of spontaneous conversations you have in that scenario, and the way they stimulate others to jump in and add their ideas, are hard to manufacture through more traditional methods.

Santini: It’s interesting that you bring up flipping power dynamics — I often see the challenges around managing power dynamics when working on research or engagement projects. As researchers or facilitators we hold a lot of power, but for me, it’s always important to flip that, as ultimately those we are working with are experts in their own experience. Co-design is a great way to make this flip, it really positions participants as experts (and therefore collaborators). But co-design is a tricky process to manage, especially when dealing with something as open-ended as cultural probes — what did you both find challenging about it?

Jo: I found the inclusivity aspect challenging — in my head I kept going back to “would everyone manage to take part in this” rather than being able to see the probes as different elements that will hopefully encompass everyone. I found it difficult to separate out my “role” within the design process from the challenges I typically encounter when carrying out research and as part of the ethics committees. I really enjoyed hearing everyone’s viewpoints and felt we could have talked for much longer but everything has to have a time limit!

Catherine: Condensing these discussions into the timeframe of a workshop was challenging. Probes can sometimes invite expansive and unexpected responses, ideally it would be nice to have more time to explore these. Being both goal-oriented and at the same time inviting creative responses is a tension — I’m not sure if this was particularly pronounced because we’re working in health research. Distilling the ideas that everyone came up with as part of the co-design process was really tricky and I think there are multiple avenues we could have gone down with the probes, but didn’t due to the process of consensus-forming. Santini, I’d be interested in how this felt from your point of view as a designer?

Santini: That’s a key tension you highlight there, and it’s one that I think most designers wrestle with, especially as the practice of design has become more and more collaborative. Inviting some kind of openness and unconstrained creativity is really useful in getting the most out of a co-design session — this is why for instance designers will often encourage all ideas, and get away from the language of ‘good ideas’ and ‘bad ideas.’ But, design as you say needs to be outcomes focussed (eventually you need to make something) which means that you need to be careful about how you direct people’s contributions. You want people to be able to input in a way that is likely to have an impact on the outcome of the work, and typically you need people to be able to see a connection between their input and some kind of output — in this case, the design of the cultural probes. Finding that balance is difficult, as is distilling the range of ideas that you are left with after a co-design session. Typically, there will be several great ideas, but once you put them through a few filters — for instance, ‘what’s feasible?’ ‘what’s going to be easy to use?’ or ‘what best addresses the project objectives?’ — the answer becomes clearer and therefore easier to build consensus around.

You said something interesting there Catherine about the impact that the domain of health research might have on the way we were working. I’d be keen to explore that a little further — how do you think health research influences the tension between goal-oriented working and creative exploration?

Catherine: I think that a lot of health research is influenced by an epidemiological orientation to the world, which seeks to categorise, standardise, and provide answers to a tightly defined question within a given set of parameters. The logic of positivism underpins this approach, which tends to sideline more phenomenological, interpretative and constructivist ways of looking at the world. Qualitative research has sought to counter these tendencies and thereby expand the kinds of knowledge we produce related to health and illness, but even so, there can be constraints on what is considered useful knowledge, which can have a chilling effect on creativity. In this particular project, which is led by a multi-disciplinary team of people from design, medicine, nursing and sociology, I hope we’ve found a balance between creative exploration and providing useful insights to help shape the future of critical care research. But a part of me wonders if we could have been more radically creative if the topic was one where there was less at stake.

Jo, any further thoughts on this?

Jo: I have little experience with qualitative research but I appreciate the constraints on the impact we can have when trying to change the way we carry out research. I see this due to the processes and procedures that are in place due to other concerns for example legal and regulatory. Those who have to take responsibility for any comeback from participants or those who consent on behalf of them have processes in place to minimise any fallout, this means that we have to operate within a set of often rigid rules and behaviours. As such the useful knowledge that we gain can’t always be applied as freely as we would hope. Working within the “what can actually be done” and “what we would like to see” is difficult, I could see how this could create tension in a collaborative group. I felt that on one hand, I was really engaging with ideas whilst on the other hand I was thinking would these be difficult to carry out within the current processes effectively? When engaging with previous ICU patients I found out those who have been involved in trying to shape other research projects have found similar constraints. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t keep advocating for change and demonstrating the buy-in from previous patients in a sensitive area for research.

Santini: I’d definitely agree that the topic (and also the target groups of participants) set some clear boundaries around how radical we can be with the research activity. When we’re researching less sensitive topics we’re generally very comfortable designing highly open-ended research activities, that really push a participant to explore the way they think or feel about something. But when working on sensitive topics such as this, there is a safeguarding component that needs to factor in. With cultural probes, we’re asking participants to complete activities on their own, without anyone from our team there to support them. With this topic, it’s likely that individuals we’re engaging have had very difficult experiences associated with the time that they or their family members have spent in the ICU, so it’s important to make sure the probes have some guardrails which avoid them straying into territory that’s triggering. Nonetheless, this will be a particularly interesting point to reflect on once everyone has completed the probes, and I’m keen to see what others think the impacts might have been if we structured them differently and whether they indeed feel like they’ve been co-designed. Let’s revisit this once they are all completed!

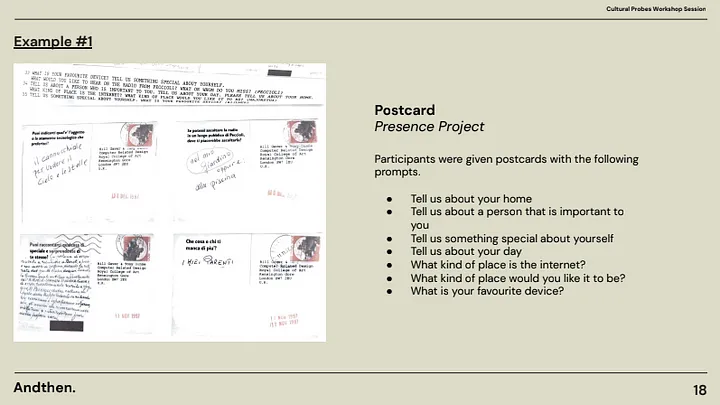

Sharing tools from our process

Some of the tools we developed to support this co-design process are available here to download for free, under a creative commons licence.

These include:

Introduction to Cultural Probes — a brief introductory presentation which outlines what cultural probes are, and gives a range of examples. Download here.

Blog 1: Cultural probes for public engagement

By Catherine Montgomery, Santini Basra, Corrienne McCulloch, Annemarie Docherty

If you’ve ever worked in or been a participant in health research, you will know that the process is one which strives for certainty in spaces where knowledge is uncertain, seeks signal over noise, and aims to follow a linear trajectory from research question to publication. In this most rational of endeavours, all parts of the process are designed with clarity, efficiency and risk-avoidance in mind: protocols dictate how the research will be conducted; ethics applications must anticipate all eventualities so as to minimise risk to participants and investigators; research tools and analysis plans must be pre-specified; the boundaries of the inquiry are set.

There are good reasons for designing and executing research in this way, most of which are to do with protecting participants and ensuring the scientific integrity of the knowledge produced. But what kind of knowledge do these processes produce when the world under study is messy, complex, and riven with ambiguity? Reflecting on social science methods nearly two decades ago, Science & Technology Studies (STS) scholar John Law wrote:

“If much of the world is vague, diffuse or unspecific, slippery, emotional, ephemeral, elusive or indistinct, changes like a kaleidoscope, or doesn’t really have much of a pattern at all, then where does this leave social science? How might we catch some of the realities we are currently missing? Can we know them well? Should we know them? Is ‘knowing’ the metaphor that we need? And if it isn’t, then how might we relate to them?”

(Law 2004: 2)

The same holds true for methods beyond the social sciences. In health research, where the randomised controlled trial holds the trophy for most highly prized knowledge, mess, instability, the ephemeral and the vague are rendered into data which is clean, complete, definite and stable. How, then, to engage the public with the ensuing knowledge, which is removed by several degrees from lived experience?

ICU-HEART is a research project funded by the Wellcome Trust, whose vision is to use routine healthcare data to improve outcomes for critically ill patients with co-existing cardiovascular disease. It aims to do this by using large national datasets to characterise patients at risk of heart attack and to design a clinical trial which will be able to show evidence of intervention effect. In ICU, around 75% of patients are admitted as an emergency, over half of these admissions take place outside normal working hours, and nearly one in five patients die in hospital. In these scenarios, most patients lack capacity to consent to treatment decisions (including participation in research) and their closest relative must give consent for participation in research on their behalf. This is a difficult task which may have significant consequences during a moment that is fraught with emotional turmoil.

Development of technology and secure mechanisms to analyse data mean that the boundaries of research and clinical care are shifting. Healthcare data that is routinely collected as part of an ICU patient’s care can now be integrated with research and used to create data sources for clinical trials. The historic emphasis on experimental research (randomised clinical trials) no longer reflects the focus of research undertaken in Critical Care, where researchers can understand much about admitted patients and their outcomes from data collected as part of their clinical care.

The potential for technological advance in relation to care and knowledge begs the question of what critical care should be like in the future: for patients and their relatives, but also clinicians, researchers and those responsible for ensuring research is ethical. Should all patients admitted to ICU contribute to research? What kind of consent, if any, should patients and their relatives give for their data to be included in studies? How does care change if a patient is involved in research?

It would not be difficult to design a questionnaire to ask people their thoughts about these issues. We could define the universe of possible responses, give people multiple choice boxes to tick, and quickly get a set of answers. Alternatively, we could conduct a smaller number of in-depth interviews exploring participants’ experiences of taking part in research in ICU and asking what they think a good model of care and consent would look like in the future. In the first scenario, the answers we get are delimited by our own conceptual universe as researchers. There is little room for things we haven’t thought of, for nuance, for ambiguity, for depth of human experience, or indeed for empathic understanding. In the second scenario, there is space for all of these things to emerge, but only within the contrived setting of the research interview. In both cases, we institute an imbalance of power, between ‘us’ the active researchers or knowers and ‘them’, the passive researched, the known.

This is not what engaged research looks like, and if we want a future ICU in which all those involved feel they have a stake, we must engage a breadth of stakeholders in articulating its design. Academics at the Centre for Biomedicine, Self and Society have been actively working on the question of engaged research for some years. In a recent paper, they stress the importance of researchers thinking through how their position in society affects the kind of knowledge they produce and the kinds of power relations it entails (Erikainen et al 2022). Implicit is an acknowledgement that all knowledge is situated, plural and partial — in other words, scientific knowledge is not a ‘view from nowhere’ but is implicated in a particular way of seeing the world from a given standpoint. There are many different types of knowledge, and each of these can provide a partial, but never complete representation of the world.

Given all of this, how could we engage different stakeholders around the question of what ICU as a place of care and research should look like in the future?

Cultural probes are a method developed in the field of design research to elicit inspiration through provocation. Consisting of visual and tangible kits that include various kinds of descriptive and exploratory tasks, such as photographing, diary-writing and collage-making, probes aim to sensitise participants to observe, reflect upon and report their experiences — while also sharing insight into their deeply held values, beliefs and ways of seeing. They offer an opportunity to disrupt the typical researcher/researched roles — probes are typically sent to participants who can complete them in their own time, in their own space, and in their own way, as activities usually are intended to be open to interpretation. “Traditional methods seem to set up a sort of game, with implicit rules limiting the relationship between researcher and researched to one addressing controlled content areas,” wrote Gaver, one of the inventors of cultural probes (Gaver 2020: 22). To counter this, probes were designed to subvert the traditional relationship between researcher and researched, allowing a conversation through which each could reveal aspects of themselves to the other. Narrating The Presence Project, in which cultural probes were first developed, Gaver describes embracing ambiguity and valuing subjectivity, leaving space for exploration, and encouraging imagination and dialogue about possible futures. This, he writes, “allowed us to work both playfully and purposefully breaking the boundaries of prevailing scientific approaches to address new values and emotions” (Gaver 2020: 11).

To us, cultural probes represent a tool for catalysing conversations between patients and relatives, clinicians, researchers, and research governance staff about the future of critical care. Existing dynamics between these different groups are characterised by entrenched power relations and protocolised ways of acting, which are not conducive to breaking the mould and imagining alternative futures. In ‘Exploring Futures for Critical Care Research’, we aim to challenge these dynamics by encouraging playfulness, embracing different kinds of knowledge, and making space for imagination as critical care moves into the data-driven era.

About ‘Exploring Futures for Critical Care Research’

‘Exploring Futures for Critical Care Research’ is funded by a Scottish Public Engagement Network (ScotPEN) Wellcome Engagement Award. The project is a collaboration between clinicians, social scientists and designers, working with ICU survivors and research governance staff to co-design cultural probes for public engagement. In addition to catalysing dialogue, the project aims to produce a set of future principles for person-centred approaches to data use and consent in ICU, as well as a public-facing installation about the future of ICU research.